How fulfilling it was to read a book that spoke to daily lived theology, with timely language that addressed the pressing questions for the Church today! What a delight as well to see the many author names of friends and familiar voices whom I have come to admire, respect, and trust.

A Living Alternative has something for everyone, and as such I will focus my review here on those sections most salient for BTSF readers. Nevertheless, there is a richness that runs throughout the book.

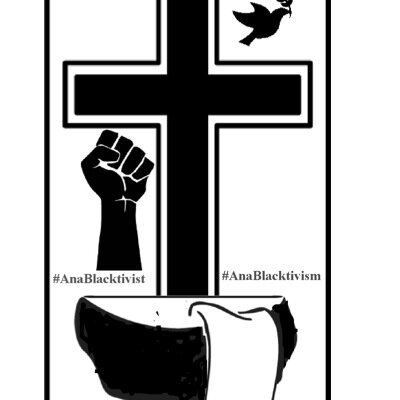

Of most central interest to the theme of this blog is the chapter by Drew Hart. He deconstructs the relationship between race and Anabaptism in his chapter 'AnaBlacktivism: Following Jesus the Liberator and Peacemaker in the 21st Century.'

Hart observes that "Christian discourse turned its head away from suffering rather than toward it. It offered no redemptive dialogue for a pained world." He questions "has Anabaptism turned its face towards dominant culture or to those that are socially marginalized and oppressed?" And he makes it clear what he believes the Church aught to be doing.

He asserts that for Anabaptists in the early 20th century, "nonresistance in the context of a non-hostile (to them because they were considered white and therefore acceptable) meant complicity." They therefore indirectly contributed to the racial violence of the time by being largely unwilling to speak out against it.

He asserts that for Anabaptists in the early 20th century, "nonresistance in the context of a non-hostile (to them because they were considered white and therefore acceptable) meant complicity." They therefore indirectly contributed to the racial violence of the time by being largely unwilling to speak out against it.Hart urges us to learn from these Christians past and to broaden our understanding of peace and justice for the Body of Christ. He notes that "the particular trouble with only focusing on or dialoguing with one's locality is that much racial injustice occurs as phenomenon larger than any one locale."

Indeed, he goes on to say that racism "is a highly complex problem that will not go away by hunkering down into local church communities, but will require a collaborative and organized ecclesiastical movement engaging in prophetic witness and nonviolent resistance to this oppressive and discriminatory force."

He notes that "the challenge of our time remains that Jesus is a white man in current American imagination, White supremacy works by making whiteness the standard for all of life, and the while male figure is that central pivot around which everyone revolves and by which everyone is critiqued."

determinatively get rid of the American Jesus, who is nothing more than a diseased projection of the ever-present white male image that dominates most of American life." He ends by encouraging us to be "proactive in antiracist work. To not do so is to be complicity in the racist system."

Along these lines, Hannah Heinzekehr notes in the very next chapter that

"In much current rhetoric and writing from Christian authors, there is a trope being employed as a way to make sense of difference and diversity. It is an idea that the goal of the future church, if it is respectful of difference and wants to transcend its segregated roots, should be to trend toward a unity found in the Kingdom of God. At their best, these statements can offer a compelling vision, which paints a picture of all God's people united in thought and action, and "singing together in perfect harmony." However, the unintended consequence of discourses like these, which seek to be more inclusive, are that they often suggest transcendence or negation of difference rather than a recognition and celebration of diversity."

She goes on to note that our temptation "is often to move towards agreement and unified church-wide understanding, even at the expense of dialogue." She describes the justice work that hospitality enables, combating the constant 'pushing out' of the marginalized and oppressed.

While not explicitly about race, also of interest are the many chapters that address how we as Christians should live in the context of society that often proclaims values that are counter to the Gospel.

While not explicitly about race, also of interest are the many chapters that address how we as Christians should live in the context of society that often proclaims values that are counter to the Gospel.Donald Clymer marries Anabaptism with St. Francis and Gutierrez. Justin Hiebert beautifully outlines principles and practices of Incarnational Living, or has he calls it, the ministry of availability. I found Joanna Harader's chapter to be particularly helpful in offering fresh approaches to to Scripture through the lenses of several women and their interactions with Jesus.

William Lowen describes why Jesus (and Christ's Church) wasn't, and shouldn't be cool, including this quote that caught my eye in particular: "I'm certain we are all inherently much more aware of our own victimization than we are of our victimizing." Important to be ever reminded.

Similarly this reminder from Samuel Wilcock was helpful as he told of his spiritual journey: "I had

thought I was growing in my faith in high school, but I came to realize I was really learning what passages I could use to argue for what I had grown to believe. While I sometimes formed beliefs based on Scriptures, I had mostly come to read Scripture in light of my beliefs."

thought I was growing in my faith in high school, but I came to realize I was really learning what passages I could use to argue for what I had grown to believe. While I sometimes formed beliefs based on Scriptures, I had mostly come to read Scripture in light of my beliefs."This remarkable group of Jesus followers, many of whom I have come to know thanks to #MennoNerds, has helped me grow deeper in my walk with Christ as they have stretched my understanding of Scripture and of living out one's faith in today's world. It is a blessing to have their collective wisdom bound together, and to have their insights in print--many of them for their first time.

All this to say, A Living Alternative is a lovely book that speaks to wide range of readers. At times intimate, at other times profound, there is much to enjoy. Read what fascinates you (and there will be much that does), and don't worry if each chapter does not affect you in the same way. The beautiful thing about this book is that it is written from many perspectives, speaking to many different situations. There is something for everyone to latch onto, and room for everyone to grow.

I am observing many in the African Amer

ReplyDelete